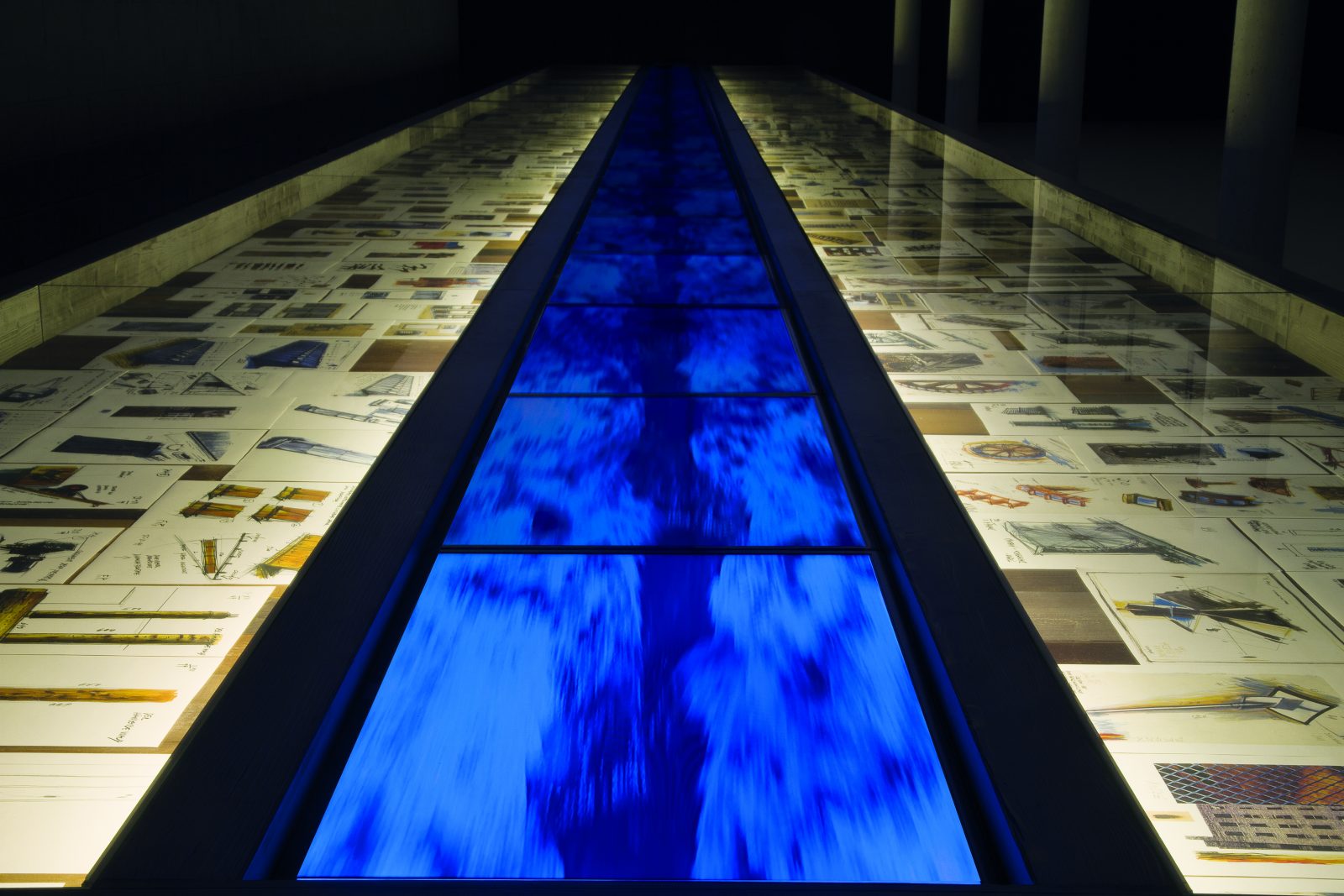

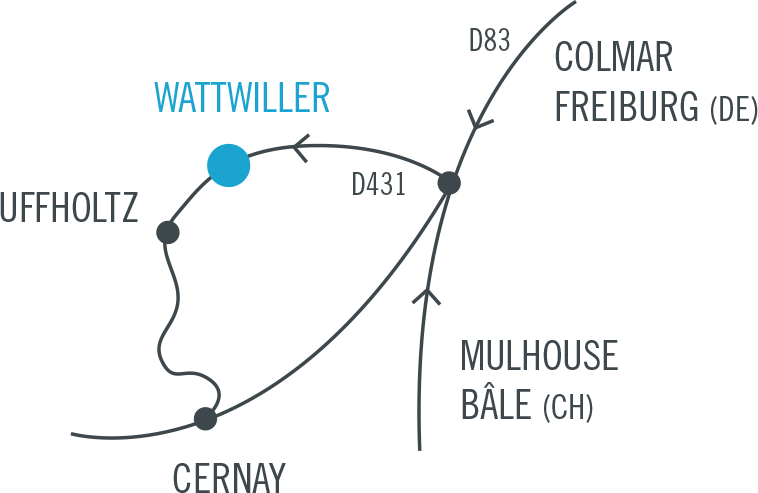

Blue and luminous, the water, transcribed into digital images, flows towards the darkness in a long straight line captivating our eyes. We get lost in this seemingly uninterrupted current and its inexhaustible stream of moving abstract motifs and are, at the same time, fascinated by the tense exchange relationship between the primitive liquid element and technology. The video sculpture Flusso illustrates in an exemplary way this link, peculiar to Fabrizio Plessi’s art, between a seductive visual language and a complex game of false pretences, where real and simulated nature are mixed. It is presented this spring at the François Schneider Foundation in Wattwiller, alongside five other major works by the artist.

Water and video are the two constants of this multimedia work that now spans five decades. Water has been central to Plessi’s creative thinking since his installation in Venice at the end of the 1960s: “that same water which, changing, charming and ambiguous, as seen from the window of my Venice studio, penetrates and dissolves everything into a liquid and fluorescent light, gradually but stubbornly becoming the real protagonist of my work. In those years, hundreds of projects centred on water, poetic and absurd at the same time, drew what the artist calls aquabiografia. These include his gigantic “emergency sponges” that saved Venice from high tide, and his Water Cage, which Plessi, who was active on the international scene from an early age, transposed into sculpture for the 1972 Venice Biennale. Video was first of all used to record his actions and performances, “on the edge of uselessness”, which resulted from this abundant repertoire of ideas and allowed him to show himself as an artist close to the Fluxus movement. Thus, in the autumn of 1973 in Paris, through a series of actions entitled Plessi-sur-Seine, he undertook to empty the Seine with a watering can.

In 1976, Mare orizzontale inaugurated the long series of video sculptures by Fabrizio Plessi. For the first time, the blue of the liquid surface is combined with the blue of the screen. From then on, these seemingly so different elements will operate an osmosis of multiple meanings: “Water and video are both liquid and have the function of transporting something […] On the screen, something flows; everything is constantly changing. The same is true of water. Both are intimately linked to the light that gives them their beauty. By making video an integral part of his work, Plessi explicitly refers to the pioneers of this technique, who have been reacting since the 1960s to the massive intrusion of the media into society. To the accelerated flow of television images, he responds with his own images slowed down to the extreme. He thus develops from the outset a calming vocabulary, limited only to the structures of water and its movements, creating a meditative atmosphere. For Plessi, it is a question of “increasing the temperature of the video by loading it with meaning and emotions. “The slow undulations of the artificial liquid surface create multiple emotions and become the support of our imagination.

The first video sculptures are also accompanied by a new predilection for simple, if possible raw materials, which testify to the artist’s affinity with the Arte Povera. In addition to Corten steel and its corroded surface, he uses stone, fabric or tree trunks, as in the imposing Foresta sospesa (Hanging Forest) presented in the centre of the exhibition. In these works, the simplicity of the material responds to the clarity of the forms, most often symmetrical. This feature is combined with a growing penchant for large installations, through the use of repetition and alignment, compositional principles inspired by minimalism, a tendency evident in Videoland (1987), also exhibited at Wattwiller.

In works frequently conceived in relation to a particular spatial context, the artist now seeks to “measure himself against a space, an environment, a history, a socio-political context”. This postmodern approach, inhabited by the need to be part of a tradition, is spectacularly illustrated with Roma, a major work created in 1987 for the documenta 8. In the same vein, in the early 1990s, with its Progetti del Mondo (Bombay, Bronx, Paris Paris) the artist proposes a theatrical staging of his perception of different contemporary urban contexts through the multiplication of everyday objects arranged in a fixed order.

This evolution is accompanied by a new role given to time, an element by nature fundamental to video art. In Tempo liquido (1989), a mill wheel, where video screens have been fixed, moves imaginary quantities of water. The water evokes the “metaphorical flow of time” (Carl Haenlein) that carries our individual and collective memories. This fundamental confrontation with time also implies, in Plessi’s work, a reflection on the history of his own creation, as witnessed by Flusso, a work already mentioned above. Thanks to innumerable photocopies of sketches and studies, the course of the water is here confronted with a fascinating journey through the meanders of a creation where, like an alchemist, the artist fuses nature, art and technology.

Viktoria von der Brüggen

Translated from the German by Jean-Léon Muller